At the start of the pandemic, makers across the country, and all over the world, came together to produce personal protective equipment (PPE).

As the world re-opens and people resume their regular jobs, the production of PPE by makers has slowed. We seem to have become complacent with supplies of face shields, masks and gowns, when desperate needs remain in hospitals, as well as the tertiary market of ambulances, mass transits, and long term facilities.

A small, but powerful, group of makers, including Artisan’s Asylum, have continued to produce PPE. This nonprofit fabrication center in Somerville, Massachusetts provided an amazing space with many resources for members to produce PPE as COVID-19 loomed.

The team grew quickly, with the majority coming from outside Artisan’s Asylum. They have a cook, a jewelry maker, a waitress, an engineer, an industrial designer, a retiree, a mathematician, a woodworker, a hotel owner, a stay-at-home mom and more. A member of Artisan’s Asylum, Michael Shia, has a son who works as a nurse. “If not me, then who?” was the phrase his son told him, and with that same mentality, Shia joined Artisan’s Asylum to help protect frontline workers against Covid-19.

They spent two weeks researching the preliminary steps to running a production line. Sarah Miller, an industrial designer, and Jay Diengott, a cook, private chef and teacher known as the Pastry Queen, swooped in to help evaluate prototypes, formulate volunteer protocols, document, research and run everything behind the scenes. Lars Torres, the executive director at Artisan’s Asylum, raised over $50,000 in total to make PPE by reaching out to banks and community partners. Shia also applied for a grant from Get Us PPE, and Artisan’s Asylum became the second recipient of the Get Us PPE Maker Grant.

All photos courtesy of Artisan’s Asylum, a nonprofit fabrication center based in in Somerville, Massachusetts.

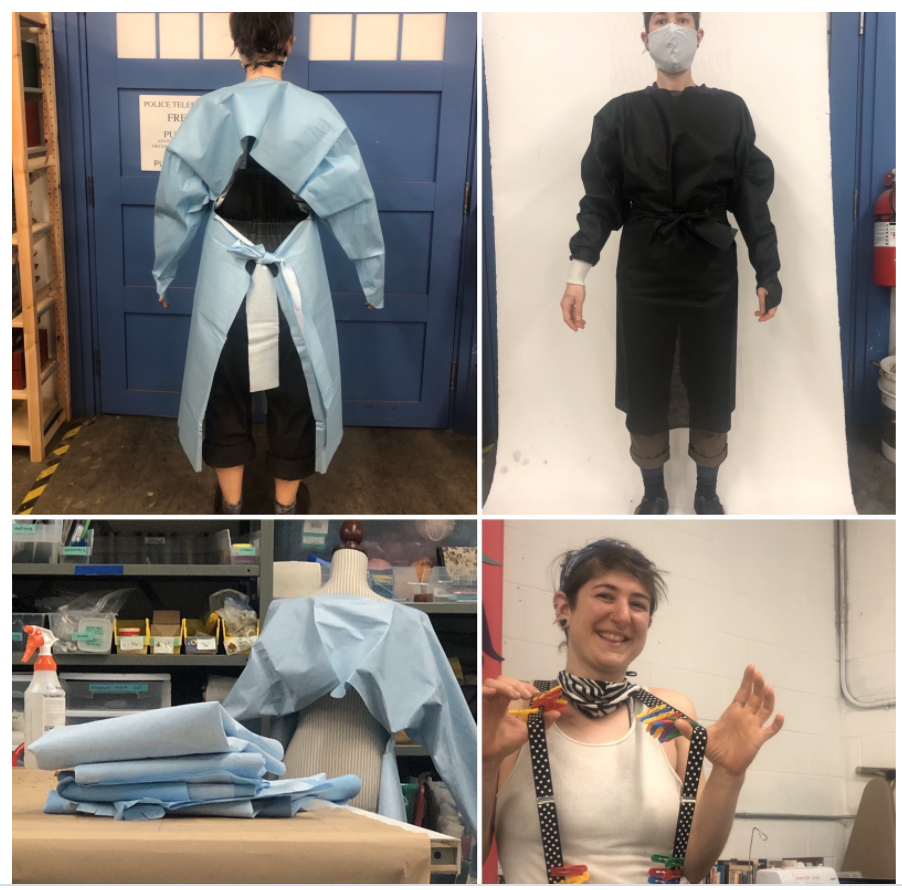

With a well-equipped team, the next step was to start producing PPE at the fastest rate possible. While masks were readily made, isolation gowns were scarce. Isolation gowns are the second most used PPE in the nation, behind gloves, yet that need hasn’t been fulfilled. Miller says, “Funding has been available by amazing organizations such as GetUsPPE, where people have donated privately to make these large funds available to makers all over the country that are willing to put their time and sweat equity into making what is now required, which in this case is isolation gowns.” Sarah Miller co-led the effort to produce these gowns. She shares that with the right medical knowledge, her team realized how easy it is to make a gown.

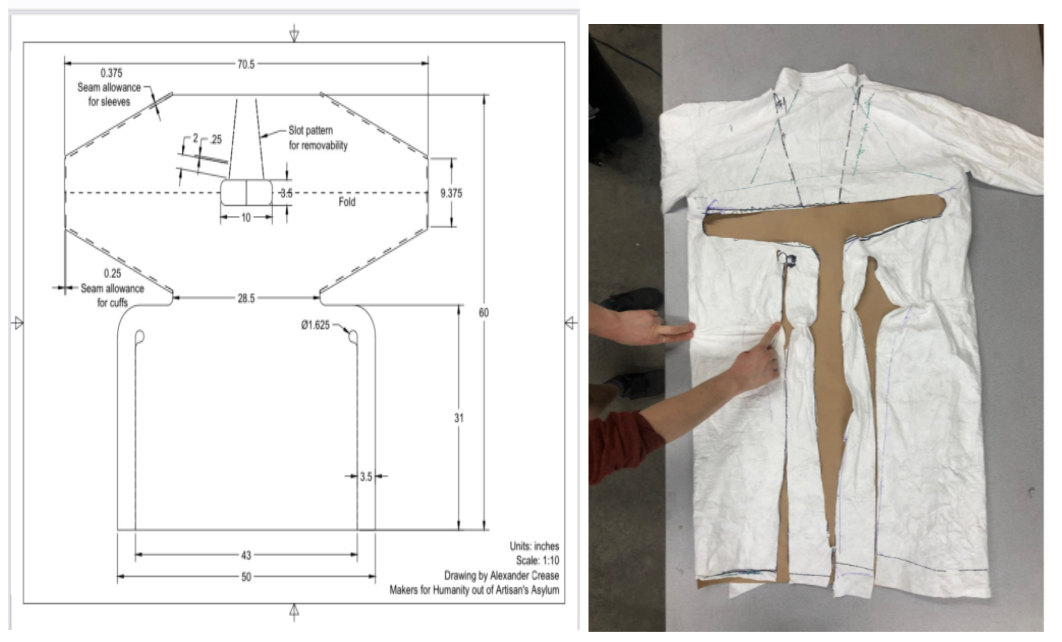

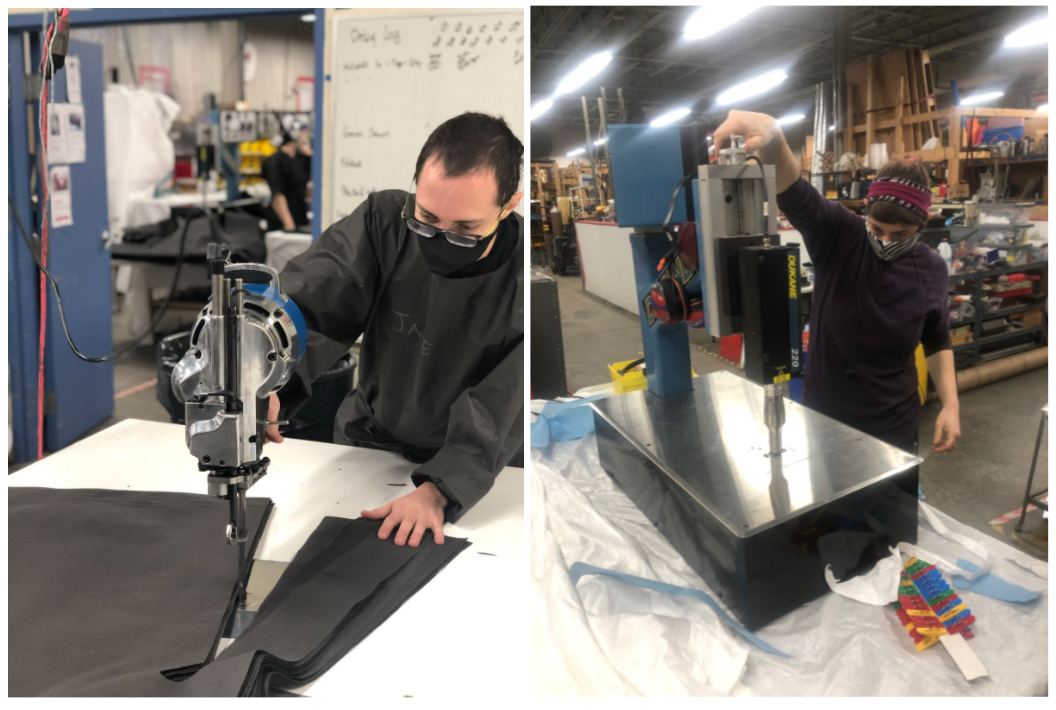

Miller says, “We started April 15 and quickly realized no sewing was required to make disposable gowns, hooray! We went to the emergency rooms of six major hospitals in order to compare patterns and materials currently used. We digitized the patterns and made prototypes from various availed materials similar to what we had found used already; 2 and 3 mL plastic sheeting, plastic backer paper drop clothes or Tyvek material. We discovered that 100% spun-bond polypropylene, even though it was not waterproof, was the closest material to what hospitals in her area were used to using. Of all the prototypes we made, the material chosen by the hospitals was landscape fabric. To bond the seams of any of these materials, it really comes down to the heating properties because the seams are all variations of plastic sheeting. Next, we reached out to our community for help and ended up with about 70 volunteers a week willing to come join us to make gowns with us. It was fun! There were five stations: rolling out, cutting, folding, bonding, and packing. We make ~400 gowns a day and will continue to increase our production throughout the week from 9 AM to 9 PM. Within 35 days, we can make almost 10,000 gowns. Most of them are going to the hardest hit hospitals like Boston Medical Center.”

Miller says, “We started April 15 and quickly realized no sewing was required to make disposable gowns, hooray! We went to the emergency rooms of six major hospitals in order to compare patterns and materials currently used. We digitized the patterns and made prototypes from various availed materials similar to what we had found used already; 2 and 3 mL plastic sheeting, plastic backer paper drop clothes or Tyvek material. We discovered that 100% spun-bond polypropylene, even though it was not waterproof, was the closest material to what hospitals in her area were used to using. Of all the prototypes we made, the material chosen by the hospitals was landscape fabric. To bond the seams of any of these materials, it really comes down to the heating properties because the seams are all variations of plastic sheeting. Next, we reached out to our community for help and ended up with about 70 volunteers a week willing to come join us to make gowns with us. It was fun! There were five stations: rolling out, cutting, folding, bonding, and packing. We make ~400 gowns a day and will continue to increase our production throughout the week from 9 AM to 9 PM. Within 35 days, we can make almost 10,000 gowns. Most of them are going to the hardest hit hospitals like Boston Medical Center.”

Going forward, Artisan’s Asylum recognizes a new, tertiary market for PPE. This market is made up of ambulance drivers, food workers or funeral home workers—people who did not initially wear PPE at work, but should consider wearing now as an added precaution. To meet growing demand, volunteers are working longer hours to help protect the community. They say being a volunteer means you are dedicating any capacity of time you have to see a project through. Returning volunteers were given free memberships to Artisan’s Asylum to reward their commitment. Miller says “We are in the barracks, and we are here to work as fast as we can as a team. It is about being a part of a larger team that is an invisible enemy and that teamwork and camaraderie was first and foremost.” The team cultivated a companionship in the workspace. They play upbeat music and give each other silly nicknames. They became a family.

Going forward, Artisan’s Asylum recognizes a new, tertiary market for PPE. This market is made up of ambulance drivers, food workers or funeral home workers—people who did not initially wear PPE at work, but should consider wearing now as an added precaution. To meet growing demand, volunteers are working longer hours to help protect the community. They say being a volunteer means you are dedicating any capacity of time you have to see a project through. Returning volunteers were given free memberships to Artisan’s Asylum to reward their commitment. Miller says “We are in the barracks, and we are here to work as fast as we can as a team. It is about being a part of a larger team that is an invisible enemy and that teamwork and camaraderie was first and foremost.” The team cultivated a companionship in the workspace. They play upbeat music and give each other silly nicknames. They became a family.

You Can Do it Too: How to Create your own Gown Production Line

Thousands are going to work without gowns because their company has never put isolation gowns as a line item, and don’t have established relationships with vendors to provide them with PPE. This would be a great pivot for folks who find themselves partially employed and have time to volunteer. Sarah Miller breaks down how you can create your own production line.

Material:

Tyvak is a material more readily available (Tyvek 1222a) which was put out by Dupont to make a very affordable and high-quality gown. Simple tools like a drill and an impulse sealer or even 3 mL plastic and a heat gun is all you need.

Production Line:

You can start to put together a production line with volunteers working 3-4 hours a day. If you hold 2-3 shifts a day, you can make 400 gowns a day and 2500 gowns a week. With a reasonable amount of effort and low-cost startup, you can make a production line yourself.

Pattern:

Patterns are readily available in packets. One resource is Open First COVID Medical Supplies, which put together a document that collates 5 different makerspaces from the US and Europe that presented 5 ways to make gowns from the tools and materials available to them. All are fast and easy, and none of them require a huge expense.

Application:

As dire COVID-19 shortages persist, the FDA has temporarily relaxed normally stringent requirements for makers to quickly distribute PPE. This should inspire other makerspaces to apply for funding through GetUsPPE, reach out to the community for donations, or go to facilities, see how much they are willing to pay, and reverse engineer that price.

Venture Out:

Speak to businesses or companies in your local area that have a need for PPE. Ask what they need and educate them on how much it will cost (oftentimes gowns are $3). Later, venture out to source the material, label the material and document.